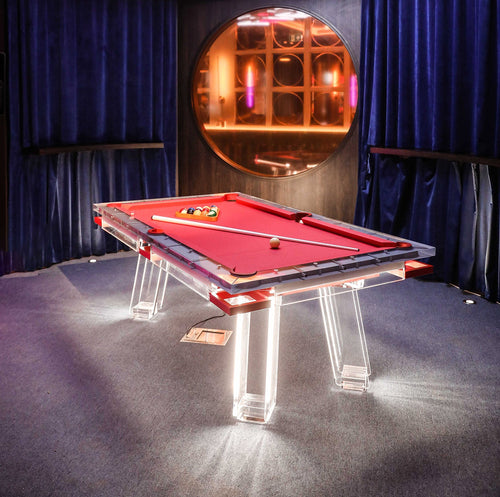

Enjoy our modern designs

Estimated Read Time: 8 mins |

China’s architectural story stretches back millennia, yet most of what survives dates only from the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Wood was the material of choice—strong, abundant, but impermanent—which means earlier buildings have vanished. Even so, the buildings that remain and those reconstructed in later dynasties reflect a design logic that evolved largely in isolation from Greco-Roman or Medieval European traditions. This parallel evolution produced an entirely different approach to structure, space, and ornamentation—one that remains unmistakably Chinese.

The Language of Timber, Brackets, and Curved Rooflines

Walk into any traditional Chinese building—temple, palace, or courtyard house—and you immediately see how the bones of the structure are celebrated rather than concealed. Massive timber columns rise vertically, carrying transverse beams that span from column to column. Walls simply fill the gaps, never claiming a load-bearing role. High above, clusters of intricately interlocking bracket blocks (dougong) fan out in graceful tiers, transferring the weight of heavy tiled roofs without a single nail or bolt. Those roofs curve upward at the eaves, their glazed tiles catching sunlight and signaling rank—yellow reserved for the emperor’s palaces, green or black for more modest dwellings. The result is a harmonious marriage of engineering and ornament, where structure and decoration are one and the same.

From Humble Courtyard Homes to the Vast Forbidden City

At the heart of traditional Chinese domestic architecture lies the siheyuan, or courtyard residence. A single gate in a masonry wall leads through a sequence of lean-to verandas into an open central court. Around this bright, open space, rooms press inward, transitioning from public reception halls in front to private family chambers at the rear. Verandas wrap the courtyard, filtering light, channeling breezes, and softening the boundary between inside and outside.

Scale up that same courtyard logic and you arrive at the Forbidden City in Beijing. Conceived in 1406 and completed within a few decades, the imperial complex strings hundreds of pavilions and halls along a perfectly straight central axis. Concentric walls and moats reinforce hierarchy and control circulation, while splash-bright red paint on thick walls and imperial-only yellow glazed roofs broadcast power and permanence.

Cross-Currents of Islamic and Western Influence

Although Chinese timber framing and bracket systems remained remarkably consistent for over a thousand years, cultural exchange did leave its mark. From the fourteenth century onward, Muslim traders and missionaries introduced Islamic decorative vocabularies. In Xi’an’s Huajuexiang Mosque, delicate geometric patterns and Arabic calligraphy appear on ceilings and walls, draped over an otherwise standard timber frame. Later, in the nineteenth century, Chinese architects who’d studied in Europe brought home Beaux-Arts eclecticism, grafting columns, pediments, and ornament borrowed from classical antiquity onto traditional silhouettes. By the twentieth century, Modernism arrived: I. M. Pei’s Fragrant Hill Hotel near Beijing uses concrete—but its rooflines and colonnades clearly nod to the bracketed forms and proportions of Ming-era villas.

Furniture: From Floor Mats to Ming Masterpieces

In early China, no furniture was needed—people sat, slept, and worked on mats spread across the floor. Over centuries, simple stools and small platforms made an appearance. By the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), a full repertoire of refined furniture existed: tall chairs with graceful horseshoe backs, lacquered tables, low cabinets, and storage chests traced in polished brass hardware. Craftsmen worked dense hardwoods such as huanghuali and zitan, fitting mortise-and-tenon joints so precisely that no nails or glue were required. The aesthetic was always one of restraint: the beauty lay in the wood’s grain, the joinery’s precision, and the minimalist silhouette.

Painting, Wallpaper, and Textiles

Beyond the bones of buildings and the lines of furniture, Chinese interiors came alive through color and pattern. Wooden beams and brackets were lacquered in vibrant reds, greens, and blues, then painted with dragons, clouds, and auspicious motifs intended to protect and uplift. With the invention of paper around the first century CE, hanging scrolls brought ink landscapes, calligraphy, and poetry into halls and chambers. By the eighteenth century, hand-painted wallpaper—depicting birds, flowers, and court scenes—became a coveted export and inspired the European craze for chinoiserie. Silk textiles draped walls and furniture, though rugs remained rare before the Ming era, when cotton warps provided extra strength for finely woven silk carpets featuring pale yellows, soft blues, and central medallions.

An East-Asian Design Family

China’s architectural and decorative traditions didn’t stop at its borders. Korea absorbed Chinese framing and bracket techniques as early as the Three Kingdoms period, adapting them in temples and palaces. When Buddhism traveled to Japan via Korea in the sixth century CE, Japanese priests and builders simply carried those same post-and-beam methods onto new soil, producing the first Japanese monasteries that closely resembled Chinese prototypes. Even the late sixteenth-century invasions of Korea by Japanese warlords sent waves of artisans back to Japan, blending local tastes with Korean refinements. Through all these exchanges, each region maintained distinct proportions, roof pitches, and decorative accents—testimony to how a core timber grammar can yield diverse dialects.

Enduring Principles

What makes China’s architectural and furnishing traditions so durable is their reliance on clear, repeatable principles rather than ever-changing styles. Exposed timber frames celebrate material honesty. Bracket clusters turn a practical necessity into ornamental art. Courtyard-centered plans adapt to scales from private homes to imperial cities. Furniture joinery mirrors building structure in miniature. Even when Islamic patterns swirl across a mosque ceiling or Modernist concrete reinvents a pavilion, the underlying logic stays unmistakably Chinese. That combination of structural clarity, elegant restraint, and a willingness to layer new influences without erasing the old is what gives this East-Asian design lineage its timeless power.