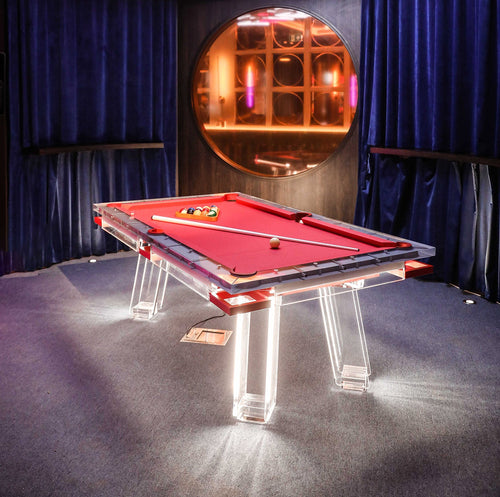

Enjoy our modern designs

Estimated Read Time: 7 mins |

Eclecticism defined late 19th and early 20th-century design not through innovation, but by meticulously selecting and recreating the past—an era of architectural and decorative pick-and-mix that still shapes our built environment.

Eclecticism—as defined in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—wasn't about innovation. It was about selection. Architects, decorators, and designers reached into the past, picked what they liked, and recreated historical styles with precision. Unlike earlier revivals or Renaissance historicism, which aimed to reimagine the past in new ways, Eclecticism's defining trait was literal reproduction—any past, as long as it could be convincingly imitated.

Why Eclecticism Thrived, Especially in America

The movement flourished in America, partly due to its lack of a long architectural history. Adopting European historical styles was a way to import culture and status. It gave visual legitimacy to banks, courthouses, churches, universities, and homes—making America feel connected to Old World grandeur and allowing cities to compete visually with Europe.

The Role of the École des Beaux-Arts

The Paris École des Beaux-Arts was ground zero for Eclecticism’s rise. Students learned to sketch and analyze historical buildings with academic precision. Though the school emphasized planning and composition, the result was a generation of architects who mastered the art of stylistic borrowing.

Architect Richard Morris Hunt, a Beaux-Arts graduate, brought this doctrine to the U.S., working in French Renaissance, Italianate, and Gothic styles depending on the project. His Biltmore Estate is pure French château; his New York townhouses echoed Renaissance design down to the ornament.

Eclecticism in Practice: Architecture and Interiors

Eclecticism touched nearly every building type:

- Churches: Gothic

- Banks & Government: Roman or Renaissance Classicism

- Homes: Anything from Georgian Colonial to Tudor or Spanish Mission

- Libraries, Theaters, Schools: All fair game for stylistic pastiche

Notable examples include McKim, Mead & White (Roman and Italian Renaissance forms), Cass Gilbert (Woolworth Building: Gothic + Byzantine interior; U.S. Supreme Court: Roman classicism), and Ralph Adams Cram (Gothic master at Princeton and French-English hybrid churches).

The Rise of Professional Interior Decoration

Eclecticism gave rise to a new profession: the interior decorator. These experts ensured a space matched its architectural style—down to the drapery tassels and furniture reproductions. Every element had to fit a recognizable period style.

Even middle-class Americans got in on it, thanks to:

- Magazines showcasing elite homes

- Furniture catalogs offering “Colonial,” “Empire,” or “Renaissance” sets

- Department stores producing “economy versions” of high-style pieces

Stripped Classicism and the Decline of Excess

After World War I, public taste shifted. Stripped Classicism emerged—classical in proportion but minimalist in ornament. Think monumental, clean lines, especially for government buildings and war memorials. This new minimalism foreshadowed modernism’s rise.

Modernism and the Death (Then Rebirth) of Eclecticism

By the 1920s and '30s, modernist designers condemned eclecticism as inauthentic and kitsch, demanding function and originality. Still, eclectic buildings remained common until after World War II—especially in conservative institutions and suburban housing.

In the postmodern era, architects like Michael Graves and Robert Venturi revived historical styles—with irony. Postmodernism quoted the past, rather than reproducing it.

Global Reach and Colonial Influence

Eclecticism wasn’t just Western. In colonial regions, European-trained architects applied styles like Gothic, Romanesque, and Classical in India, Africa, and Southeast Asia—offering comfort to colonists and subtly introducing Western aesthetics into new contexts.

Conclusion: Eclecticism as Cultural Mirror

Eclecticism reveals more about its era than any one style. It reflects the anxieties of new wealth seeking legitimacy, the desire to link past glories to modern institutions, and a belief that design authority lay in imitation. It was opulent, theatrical, and often deeply nostalgic. And though dismissed by modernists, its fingerprints are everywhere—from city halls to brownstones to Main Street storefronts.