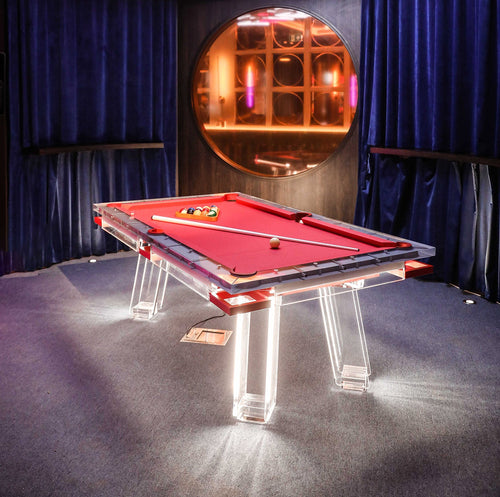

Enjoy our modern designs

Estimated Read Time: 5 mins |

In an age of Victorian excess, Shaker Design stood apart—unornamented, utilitarian, and rooted in spiritual purpose. What began as a religious discipline evolved into a design legacy that still inspires minimalists and modernists alike.

Origins: Belief as Design

The Shakers, a religious sect from England, arrived in America in 1774 seeking religious freedom. Their lives were structured by communal living, humility, and celibacy, principles that shaped their approach to design. Guided by the doctrine: “Put your hands to work and your hearts to God.” Their Millennial Laws outright banned decorative flourishes—“Beadings, mouldings and cornices which are merely for fancy may not be made by believers.” Every line and join had to justify itself.

Style: Aesthetic of Function

- No ornamentation—walls were white or painted in muted tones.

- Wooden floors, practical and unadorned.

- Banks of built-in drawers for seamless storage.

- Horizontal peg rails across rooms to hang tools, coats, even chairs.

Shaker design was about utility first. Yet, within that utility was quiet beauty—balanced, well-proportioned, and enduringly crafted.

Craftsmanship: Honest and Ingenious

- Ladder-back chairs with woven tape seats—icons of American design.

- Tables, benches, cabinets, and boxes—all meticulously built.

- Innovative cast-iron stoves and handwoven baskets and textiles.

Lacking formal aesthetic training, Shakers created works defined by proportion, rhythm, and integrity—modernist minimalists before the term existed.

Context: Outliers of Taste

While Victorian America reveled in velvet, fringe, and ornate décor, Shaker communities rejected outside trends as “Babylon.” To them, ostentatious furniture was a spiritual liability. Despite this, Shaker chairs found buyers beyond the community, admired for their clean lines and practicality.

Legacy: From Ascetic to Avant-Garde

Shaker design reached its peak refinement in the 1830s. While mainstream styles cycled through Colonial, Georgian, Federal, and Victorian exuberance, Shakers remained steadfast. Their work gained appreciation in the 20th century, inspiring Modernist designers like Paul McCobb and influencing both Scandinavian and American minimalism.

Enduring Relevance

Today, preserved sites in Hancock (MA), Pleasant Hill (KY), and Sabbathday Lake (ME) showcase the Shaker ethos. Their pieces are valued not just for rarity, but for embodying purpose-driven design—rejecting ego and excess in favor of clarity and function.

Shaker design was never meant to impress. It was meant to serve. Yet in serving honestly and beautifully, it became timeless.