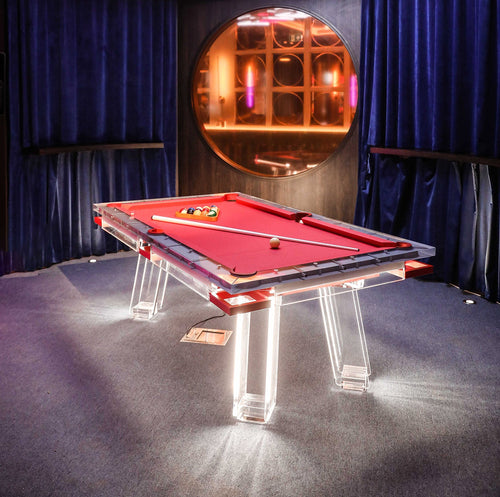

Enjoy our modern designs

Estimated Read Time: 6 mins | June 4

How the École des Beaux-Arts set the template for American prestige, blending classical grandeur with eclectic, history-rich architecture.

By the late 19th century, American architecture was no longer searching for a native voice—it was importing one. That voice came from Paris, and it spoke in columns, cornices, and château roofs. The École des Beaux-Arts, the premier architectural school in France, sent ripples through American design culture that would echo well into the 20th century. This movement—called the Beaux-Arts invasion—was a critical force in embedding Eclecticism into American architecture and shaping what prestige and refinement looked like in the U.S.

Eclecticism Takes Root

Eclecticism is the practice of drawing on multiple historical styles and imitating them with high fidelity. Unlike earlier historicism, which reinterpreted history to suit the present, Eclecticism's goal was convincing reproduction. In America, this made perfect sense. The country lacked a deep architectural past to draw on, and the newly rich were eager to buy their way into the European tradition—or at least decorate their homes as if they had.

Enter the École des Beaux-Arts

The École des Beaux-Arts in Paris was the world’s most influential design school during this era. It trained students through an intense system that emphasized:

- Historical knowledge, especially classical monuments

- Rigorous drawing and composition

- Structured design problems ("programs") judged by juries

The school didn’t explicitly teach imitation—but its focus on monumentality, formal balance, and classical detailing made it the perfect pipeline for Eclectic architecture in practice.

Richard Morris Hunt: The Vanguard

Richard Morris Hunt was the first American to train at the École (1846–1855), and he brought that education back to New York with missionary zeal. More than just a gifted designer, Hunt was a tastemaker. He applied his Beaux-Arts training in a deeply imitative way, adapting European models for America’s rising elites:

- For William K. Vanderbilt, Hunt created a Manhattan townhouse styled after a French Renaissance château.

- In Newport, he designed Marble House, a mansion with interiors evoking the splendor of Versailles.

- At Biltmore Estate, he scaled up French château aesthetics to near-mythic proportions, delivering on a client’s fantasy of royal grandeur.

Hunt’s greatest legacy wasn't any single project—it was his normalization of imitation as a design philosophy. He set the precedent: American prestige architecture didn’t just borrow from the past, it embodied it wholesale.

Beaux-Arts America: Monumental Vision

Nowhere was Hunt’s influence more visible than at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. As part of the board of architects, Hunt and his peers envisioned a "White City" filled with monumental, classically inspired buildings organized around a lagoon. Hunt’s Administration Building, with its imposing dome and classical detailing, embodied the Beaux-Arts aesthetic—and made competing visions, like Louis Sullivan’s Art Nouveau, seem awkwardly out of step.

The fair captivated Americans. Its style became the blueprint for future city halls, libraries, train stations, and museums. The idea that grandeur = historical imitation became gospel.

The Double-Edged Sword of Beaux-Arts Influence

While the original École des Beaux-Arts emphasized planning and proportion over pastiche, American practice veered hard into stylistic mimicry. Hunt, in particular, found his strengths in reproducing historic forms, not in solving new design problems. His Tribune Building, one of America’s early skyscrapers, struggled to reconcile verticality with historical precedent—revealing the limits of imitation in a changing world.

Still, the Beaux-Arts model dominated American architectural training and professional standards well into the mid-20th century. Its impact was felt in:

- Design schools, which adopted Beaux-Arts methods

- Professional licensing, which emphasized classical drafting and planning

- Public buildings, which overwhelmingly favored monumental, classical styles

Legacy: Echoes and Backlash

Eventually, modernists rebelled against Beaux-Arts and Eclecticism alike. They criticized it as aesthetic cosplay—beautiful but backward-looking, more interested in nostalgia than innovation. And yet, even as modernism rose, the Beaux-Arts legacy lingered.

Its discipline, proportion, and formal rigor still inform architectural education. Its buildings—grand, orderly, and built to last—still anchor cities across the U.S. The Beaux-Arts invasion might have ended, but it redrew the map of American design.