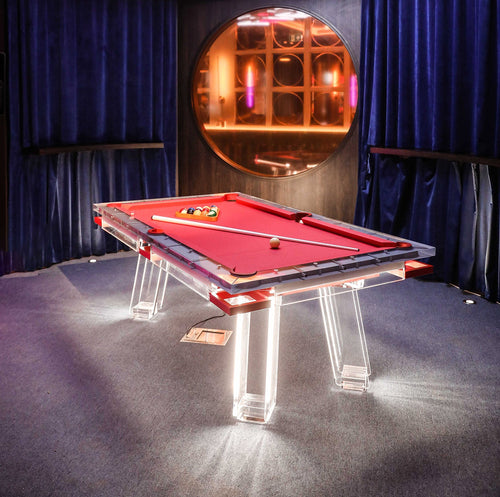

Enjoy our modern designs

Design History Deep Dive |

Eight decades, countless movements. From glass boxes to algorithmic facades, here’s how American design stayed restless, adaptive, and always experimental.

The Post‑War Boom and the Ascendancy of Modernism

The G.I. Bill pumped money into new universities, hospitals, and corporate headquarters. Wartime material restrictions lifted. America needed buildings—fast—and modernism offered speed, clarity, and a clean break from pre‑war eclecticism.

- International Style as Default: Flat roofs, rational structure, and curtain walls became the professional baseline.

- Glass‑Walled Skyscrapers: Power brokers signaled success with facades of uninterrupted glazing. Miles of stainless steel mullions defined skylines from New York to Chicago.

- Office Landscape (Bürolandschaft): Management consultants promoted open plans and modular furniture. Ergonomic seating evolved from afterthought to necessity.

Headline Names (1945‑1965):

- European émigrés: Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Alvar Aalto

- Home‑grown modernists: Eero Saarinen, Philip Johnson, I.M. Pei, Pietro Belluschi

- Corporate heavyweights: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM)

- Outlier legend: Frank Lloyd Wright, still innovating with the Guggenheim (1959)

Furnishing the Modern Age

Early adopters complained that the market lagged behind their sleek buildings. Two manufacturers filled the gap:

- Knoll: Introduced Breuer’s tubular steel chairs and Saarinen’s womb‑like lounges.

- Herman Miller: Backed Charles & Ray Eames, George Nelson, and Harry Bertoia; eventually rewrote office ergonomics with the Aeron.

Designers Who Became Household Names:

- Marcel Breuer – Cesca chair

- Mies van der Rohe – Barcelona collection

- Eero Saarinen – Tulip series

- Charles & Ray Eames – Lounge & Ottoman, molded plywood line

- Jens Risom, Paul McCobb, Edward Wormley – democratic modernism for the masses

Textiles followed suit: solid hues, restrained geometrics, and durable synthetics that matched the era’s optimistic pragmatism.

Modernism Under Fire (Late 1960s‑1970s)

By the 1970s, critics labeled endless glass slabs “soulless.” Energy crises exposed their thermal inefficiency. Designers splintered into new camps.

High‑Tech

- Celebrated structure and services as honest aesthetics. Buckminster Fuller’s geodesics gained fresh relevance; Norman Foster’s exposed ducts made engineering sexy.

Post‑Modernism

- Color, ornament, and historical irony returned.

- Robert Venturi: “Less is a bore.”

- Michael Graves: Portland Building, Disney’s Swan & Dolphin Hotels.

- Philip Johnson: Swapped his glass box for a Chippendale‑crowned AT&T tower.

Deconstructivism & Radical Minimalism (1980s‑1990s)

- Frank Gehry: Chain‑link experiments in Santa Monica, later the titanium‑clad Bilbao effect.

- Peter Eisenman: Fragmented geometries that challenged spatial norms.

Late Modern & Individualists

- I.M. Pei: Sculpted monumental clarity (Louvre Pyramid).

- Philippe Starck & Andrée Putman: Flamboyant, witty, often unclassifiable objects and interiors.

Cultural Cross‑Pollination and the Museum Boom

Japan’s Arata Isozaki and Yoshio Taniguchi landed major U.S. commissions, underscoring a two‑way exchange of design ideas. Meanwhile, institutions raced to attract visitors with architect‑driven statements:

- Getty Center, Los Angeles – Richard Meier (1997)

- Guggenheim Bilbao – Frank Gehry (1997)

- SFMOMA – Mario Botta (1995), expanded by Snøhetta (2016)

These projects turned lobbies and galleries into civic living rooms and tourist magnets.

Preservation, Sustainability, and Social Impact

- Abandoned warehouses reborn as lofts, train stations converted to hotels, and an official push to protect mid‑century landmarks.

- Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) seeded an environmental conscience that matured into LEED, WELL, and a material‑health movement.

- Adaptive reuse conserved embodied carbon before the term existed.

- Designers embraced daylighting, recycled content, and low‑VOC finishes.

- Social‑impact design aimed at underserved communities, from affordable housing prototypes to healthcare interiors prioritizing patient dignity.

Twenty‑First‑Century Design: A New Playing Field

Today, “American design” is a misnomer—geography matters less than bandwidth. Teams span time zones; projects appear in real‑time Building Information Models.

Key Drivers

- Global Collaboration: U.S. studios tackle airports in Doha while Danish firms retrofit New York offices.

- Technology: VR walk‑throughs, parametric facades, AI‑optimized floor plates.

- Sustainability: Net‑zero targets, mass‑timber skyscrapers, circular‑economy furniture.

- Social Welfare: Trauma‑informed schools, inclusive stadia, brand spaces that double as community hubs.

Stylistic Threads

- Mainstream Modernism – still the default corporate vernacular.

- Biomorphism – fluid, nature‑inspired forms via 3‑D printing.

- Color Craftsmanship – bold palettes replacing the 2010s’ grayscale minimalism.

Buildings range from libraries (OMA’s Seattle Central), to health‑care villages (MASS Design Group), to flagship retail (Apple’s glass‑box evolutions by Foster + Partners).

Conclusion: More Directions, One Imperative

From wartime austerity to algorithmic facades, American design has diversified without losing its experimental core. The common thread is problem‑solving—whether the problem is speed of construction in 1947, energy consumption in 1973, or carbon footprint in 2025. The result is a restless, adaptive discipline continuously rewriting its own rulebook—and, in the process, the spaces where we live, work, and dream.