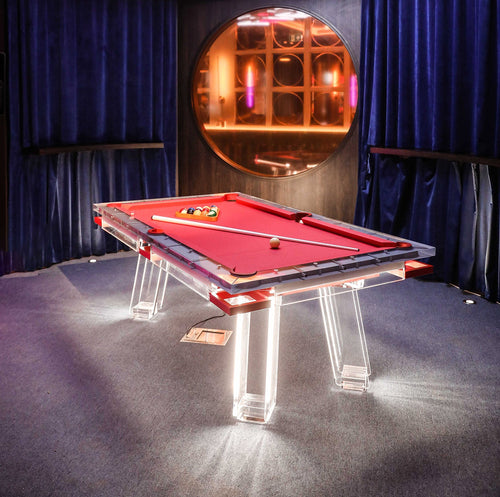

Enjoy our modern designs

Estimated Read Time: 9 mins |

The Early Renaissance in Italy, beginning around 1400 in Florence, marked a profound shift in interior design that paralleled changes in art, architecture, and philosophy. Fueled by wealth from trade and banking, Florence became a fertile ground for the revival of classical ideas. This revival was not about nostalgic imitation but rather an ambitious reimagining of antiquity through the lens of Humanism.

Humanism emphasized individual potential, personal achievement, and empirical inquiry. With it came a growing awareness of history, the importance of authorship, and a turn away from the medieval focus on spiritual salvation toward a worldly celebration of knowledge and beauty. This intellectual shift directly impacted how spaces were designed, decorated, and inhabited.

Early Renaissance Interiors: Classical Influence and Experimentation

In Florence, the town palazzo emerged as a new residential form for the elite, replacing medieval fortresses with more open and symmetrical designs. A typical palazzo was a multi-storied structure with a ground floor for storage and services, a piano nobile for formal and private rooms, and upper floors for servants. Interiors were planned with clear attention to classical ideals: symmetry, proportion, and order.

Walls were typically smooth, painted, or adorned with frescoes. Ceilings might be beamed or coffered and often richly colored. Floors featured patterned brick, tile, or marble. Fireplaces were embellished, and decorative accessories—such as tapestries and drapery—reflected wealth and taste. One preserved example from this transitional moment is the bedroom of the Palazzo Davanzati in Florence, which showcases a tiled floor, painted beams, and frescoed walls with restrained furnishings.

The Rise of Classical Vocabulary: Brunelleschi and Interior Architecture

Filippo Brunelleschi was a pivotal figure whose interior designs brought classical Roman language into Florentine churches. His work at S. Lorenzo and S. Spirito featured geometric grid planning and the use of Roman arches supported on Corinthian columns with impost blocks—a hybrid solution seen in Early Christian and Byzantine architecture. The Old Sacristy at S. Lorenzo and the Pazzi Chapel at S. Croce further exemplify his measured application of classical elements like domes, pilasters, and symmetrical layouts.

These interiors were serene, mathematical, and harmonious. Walls were delineated with pilasters and rondels; domes crowned balanced square or rectangular plans; colors were restrained to gray-green and white. Brunelleschi’s spaces, though tentative in their classical understanding, established a new architectural rhythm that would define Renaissance interiors.

Decoration: Fresco, Stucco, and Illusion

As Renaissance interiors became more sophisticated, so did their ornamentation. Fresco painting, influenced by Early Christian and Byzantine mosaics, gained prominence. Giotto's frescoes at the Arena Chapel in Padua laid early groundwork, while Benozzo Gozzoli's Procession of the Magi at the Medici-Riccardi Palace offered vibrant, tapestry-like wall coverage.

During the High Renaissance, fresco techniques matured. Entire walls and ceilings were painted to simulate architecture and mythological scenes, as in Annibale Carracci's work in the Farnese Palace. Stucco—sculpted and painted plaster—augmented three-dimensional illusions. By the Mannerist and Baroque periods, decoration became even more theatrical and complex, merging painting and sculpture into immersive environments.

Palaces and Villas: Status and Symmetry

Palaces like the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi and Palazzo Farnese illustrated evolving notions of urban prestige. These buildings employed classical courtyards, symmetrical facades, and increasingly refined Roman details. Interiors featured formal reception rooms, frescoed salons, and richly adorned private chambers.

Country villas offered a parallel development. Andrea Palladio's villas in the Veneto, such as Villa Rotonda and Villa Barbaro, merged temple architecture with domestic needs. Interiors used central plans with mathematically derived proportions, while frescoes (notably by Veronese at Villa Barbaro) added visual depth and narrative.

Furniture and Functional Design

Furniture shifted from medieval austerity to Renaissance elegance. New forms such as the cassone (chest), cassapanca (bench), and a range of chairs and tables appeared. Woods were carefully crafted with fine joinery, and lacquered finishes added polish. Beds became more elaborate, often with canopies and curtains.

Lighting, textiles, and mirrors (especially in Venice) added comfort and luxury. Interiors were no longer just spaces for shelter but arenas for intellectual, cultural, and aesthetic expression.

Conclusion

Interior design during the Italian Renaissance marked the convergence of revived classical ideals with evolving social conditions. Whether in palatial urban residences or countryside villas, interiors reflected a growing emphasis on harmony, beauty, human scale, and rational planning. From Brunelleschi's early experiments to Palladio's perfected villas, Renaissance interiors laid the groundwork for centuries of design innovation rooted in classical humanism.