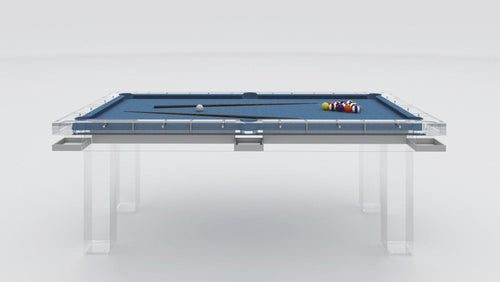

Enjoy our modern designs

Estimated Read Time: 5 mins |

How a bold tastemaker turned interior decorating into a profession and changed the way America lives with style and light.

From Stage Actress to Style Icon

Before entering the world of interiors, de Wolfe was a stage actress and socialite. Her transition into decorating began organically—by transforming her own home. Victorian interiors at the time were known for their heavy drapery, dark wood, and visual clutter. De Wolfe painted walls white, introduced cheerful pastels, added light floral chintzes, and replaced the gloom with air and light. Her signature? A look she called "stylish simplicity"—a bold departure from the excess of her era.

High Society’s Go-To Tastemaker

Her refreshing style caught the attention of her influential circle. Friends and guests began asking for her help with their homes. Soon, de Wolfe found herself professionally decorating for the American elite.

Notably, she was commissioned by Stanford White, one of the most prominent architects of the time, to help with residential interiors and the New York Colony Club (1905–07). Her influence spread even further when Henry Clay Frick hired her in 1913 to design the family quarters of his Fifth Avenue mansion. Here, de Wolfe incorporated French antiques and set them against bright, light-filled backdrops—always with her trademark restraint.

From Simplicity to Historicism—With a Twist

Although her early style rejected heavy historical imitation, the nature of her high-society clientele—who lived in homes designed with overt historical references—inevitably pulled her into period-style decorating. Yet even when leaning toward historicism, de Wolfe never succumbed to strict replication. Instead, she curated eclectic environments that nodded to 18th-century French and Colonial American aesthetics without copying them outright.

An iconic example: her dining room on Irving Place in New York. It replaced Victorian fuss with wallpapered surfaces, white-painted moldings, clean-lined furniture, and subtle references to the past—refined, restrained, and undeniably modern.

Publishing Her Vision

In 1913, de Wolfe published The House in Good Taste, a manifesto for her design philosophy. It reached a broad audience and helped cement her influence. At the same time, magazines like House Beautiful and House and Garden began showcasing her work, amplifying the idea that stylish interiors should reflect a recognizable “period style”—Colonial, Spanish, French, or otherwise.

This marked a pivotal shift in American taste: every room should have a style, and that style should be informed by history—even if only loosely.

Legacy: The First Professional Decorator

Elsie de Wolfe wasn’t just decorating rooms—she was designing a profession. Her ability to mix simplicity with glamour, her understanding of space, light, and comfort, and her willingness to borrow from history without being confined by it made her a pioneer.

She opened the door for countless decorators after her and left a legacy visible in every white-painted trim, floral chintz, and elegantly eclectic room that dares to be both timeless and fresh.